the matterhorn conquered

Pennine alps

zermatt, canton of valais

border between italy & switzerland

Europe

July 14, 1865 and ever since ...

the matterhorn conquered

Pennine alps

zermatt, canton of valais

border between italy & switzerland

Europe

July 14, 1865 and ever since ...

Every time Henry and I have been in Zermatt, I have been amazed that he had indeed climbed the Riffelhorn, the Rothorn and the Matterhorn in 1953*1. The isolated nature of the Matterhorn, its shape with horn and cliffs, its height at 4,478 meters/14,692 feet, and its prominence above the immediate surrounding pinnacles, topping them by 1,040 meters/3,412 feet, is truly formidable. In 1865, the Matterhorn was the last of the great Alpine peaks to be conquered, and its first ascent marked the end of the golden age of alpinism. The party of Edward Whymper, Charles Hudson, Lord Francis Douglas, Douglas Robert Hadow, Michael Croz, and the guides, the two Peter Taugwalders (father and son) was able to reach the summit by an ascent of the Hömli ridge in Switzerland. Edward Whymper and his fellow alpinists were all British, and it was Whymper’s seventh attempt to conquer the Matterhorn. The Matterhorn is one of the deadliest peaks in the Alps. In fact, on the triumphal conquest of the mountain, four of the climbers fell to their deaths on their descent. In 1881, Theodore Roosevelt, American President 1901-1909, climbed the Matterhorn with two guides, and in a letter dated August 5, 1881, addressed to his sister, Bysie, described it as a “mountain so steep that snow will not remain on the crumbling, jagged rock, and possesses a certain sombre interest from the number of people that have lost their lives on it. Accidents, however, are generally due either to rashness, or else to a combination of timidity and fatigue, a fairly hardy man, cautious but not cowardly, with good guides, has little to fear. Still there is enough peril to make it exciting, and the work is very laborious, being as much with the hands as the feet and (very unlike the Jungfrau) as hard coming down as going up. ... it was like going up and down enormous stairs on your hands and knees for nine hours”. Between 1865 and 1995, five hundred people died on the Matterhorn.*2 The North Face wasn’t climbed until 1931, and it is amongst the six great north faces of the Alps. The four steep faces, rising above the surrounding glaciers indicate the four compass points. The mountain overlooks the town of Zermatt in the canton of Valais and stands in the Pennine Alps on the border between Switzerland and Italy. The Italian name for the mountain is Monte Cervino, and the French name is Mont Cervin. The Matterhorn has become an iconic emblem of the Swiss Alps and the Alps in general. Since the end of the 19th century, when railways were built, and even until today, many visitors and climbers have been attracted to Zermatt, in the winter to ski, and in the summer to hike and climb, some attempting the climb of the Matterhorn.

1In the summer of 1953, between their Sophomore and Junior years at Harvard, Henry and his roommate, John Chatfield drove around Europe. It was John’s suggestion that they climb the Matterhorn in July, based on his brother’s experience before him. John had been introduced to August Julen, a mountaineer guide and a member of one of the founding families of Zermatt. Henry went along with the idea, and they both enrolled in a climbing course. Henry was assigned a guide, another prominent Zermatt family member, Edward Biner (pronounce “Beaner”). The first day of their course was spent learning climbing techniques on the Riffelhorn. The next day, they applied those techniques to a climb of the Rothorn, and the following day they began their ascent of the Matterhorn. Henry told me that the first part of the climb, across the moraine, huge fields of irregular rocks and boulders deposited by glaciers, was the most tiring part of the journey. The climbers and their guides spent the night in Hömli Hut, had a light repas, went to bed early, and arose between 2 and 3 AM to begin the ascent. Henry remembers with some amazement how the stars in the night sky lit their path. The guides more than likely took the party up the north-eastern Hömli Ridge, the most popular route to the summit. John Chatfield and Henry Ziegler stood atop the great horn that morning, and made their descent early to avoid the danger of avalanches.

2 Research to compare the Matterhorn death toll with the Mt. Everest death toll, (500 vs 216 respectively). found that the Matterhorn deaths at 500 over a 135 year period (equaling 3.7 per year) to be higher in number than the deaths on Everest at 216 lives claimed in an 88 year period (equaling 2.45 per year). Approximately 150 bodies have been left on Mt. Everest since the 1921 exploratory expedition lead by George Mallory of Great Britain. In the British Everest Expedition of 1922, an avalanche killed seven sherpas. In 1924, George Mallory chose Andrew Irvine as his climbing partner in the attempt to conquer Everest, and both died. Mallory’s body was found in 1999, and it is believed that he reached the top, then fell and broke his leg. In another British mission to conquer Everest, Sir Edmund Hillary and the Nepalese sherpa, Norgay Tensing, succeeded in reaching the summit in 1953. Both also successfully made the descent. Since then, have been over 4,102 ascents of Mt. Everest by about 2,700 individuals as of 2008. The total death count on Everest as of 2009 is 216.

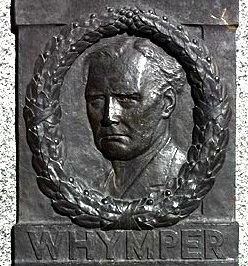

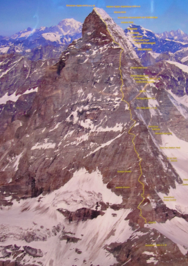

PHOTOS: Left Column: 1. Early morning photo of the Matterhorn taken on January 5, 2010. 2. The First Ascent of the Matterhorn, an etching by Gustav Doré. 3. A model of the Matterhorn depicting the route discovered in 1931, the most popular route used to climb the mountain since that date. Center, Top: 19th century poster advertising the train service from Paris to Zermatt in just 20 hours! Center, Middle: A plaque of on the Hotel Monte Rosa in Zermatt. It states that Edward Whymper left this hotel on July 13, 1865, successfully conquering the Matterhorn on July 14, 1865. Center, Bottom: Peter Taugwalder, at the age of 79. He was the mountaineer guide on the first ascent of the Matterhorn on July 14, 1965. In The Matterhorn Museum is a vitrine exhibiting the rope that broke between Douglas and Taugerwalder on the first conquest of the Matterhorn. On July 14, 1965, Michael Croz Douglas, Charles Hudson, Lord Francis Douglas, and Douglas Robert Hadow fell to their deaths. Taugerwalder returned to Zermatt with the rope as proof that it hadn’t been cut, as rumors had implied. The jute rope had obviously been stressed by the weight of the falling climbers, and the sharpness of the rocks frayed the material. Right Column: 1. The Matterhorn at sunset on January 11, 2011. 2. An etching by Gustav Doré entitled “The Matterhorn Tragedy”. The top figure, representing Taugerwalder as guide, holding the frayed rope. 3. The Matterhorn with the route on the north-east face in a zig-zag path to the pinnacle. This is the route discovered in 1931, the most popular route used to climb the mountain since that date.

Photo Credit: Left Column #2, Center, Middle & Right Column #2: Courtesy of Wikipedia Creative Commons Share Alike.

Iconic Alpine Mountain